A Frogs Are Green eco-interview with Nick Massimo and Evan Brus.

When was your organization founded? Please tell us a bit about its/your mission, goals… When did you first begin this important work?

Evan and I are both PhD students studying the disease dynamics of a deadly fungal pathogen that infects amphibians all over the world. The pathogen is Batrachochtrium dendrobatidis (Bd), and it causes the disease called chytridiomycosis. This disease was first noticed in the late 1980s and early 1990s as a wave of mass amphibian mortality events swept through Central America. Further research linked Bd to mass amphibian die offs and the extinction of multiple amphibian species all over the world.

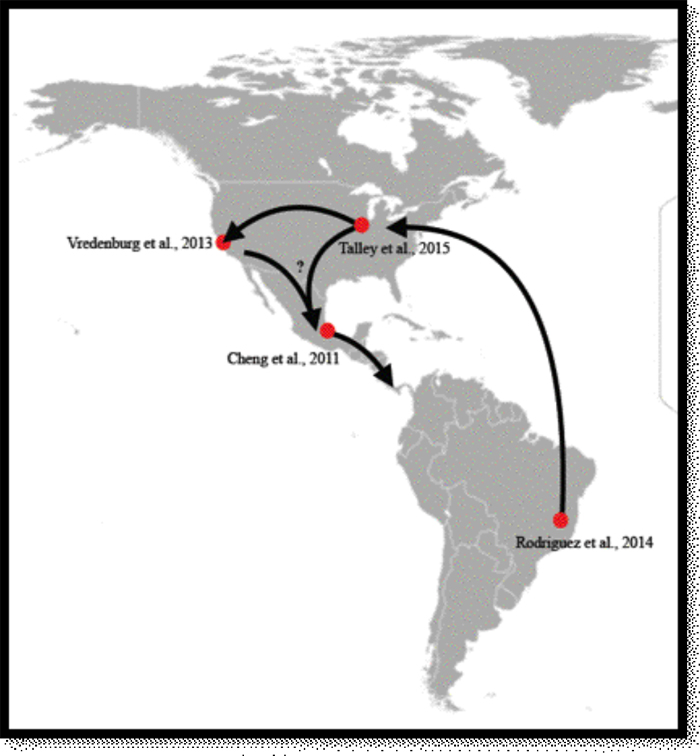

Recent research has created a picture of how this pathogen may have originated in Brazil and spread to North America over 100 years ago. The oldest amphibian specimen that’s tested positive for Bd was in Illinois in 1888. Then, in the 1920s Bd was detected in California. Approximately 50 years passed before Bd was detected again in southern Mexico in 1972. The detection of Bd in Mexico was then tracked south into Central America where researchers first noticed the dramatic effects Bd could have on amphibian communities. The goal of our project is to better understand how Bd spread in the Americas, possibly passing through Arizona and to determine how this pathogen has impacted Arizona’s numerous amphibian species.

What is your educational background and what lead to wanting to specialize in this area and/or create your organization?

Nick Massimo

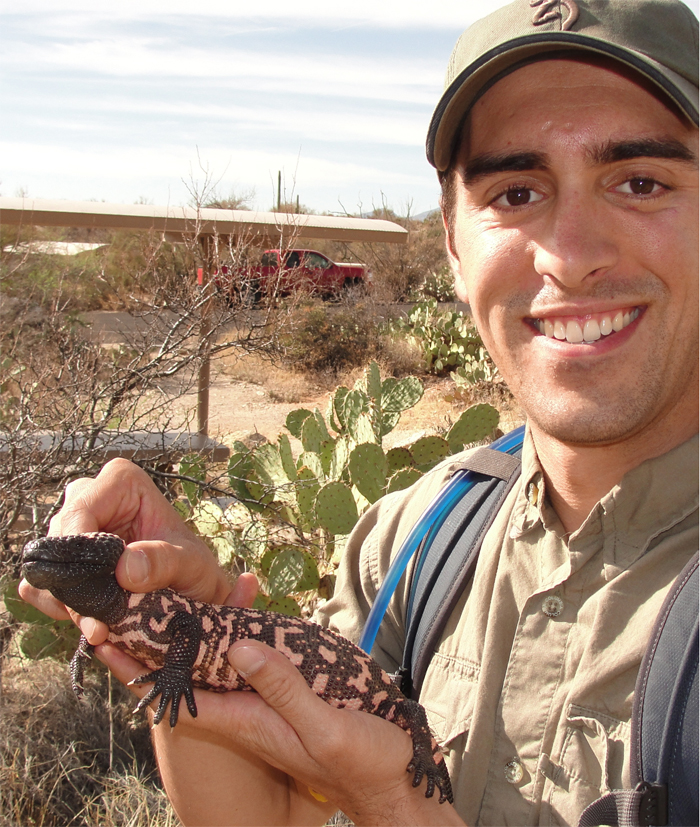

I received a BS in biology and nutritional sciences and a minor in chemistry from the University of Arizona in 2011. After I graduated with my BS I spent two years working on numerous research projects studying species such as the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), desert tortoises (Gopherus agassizii), fungal endophytes (fungi that live inside plants), and several other herpertofauna species from the southwestern United States. I gained these experiences working with the University of Arizona, the Arizona Game and Fish Department and a not-for-profit group, Friends of Saguaro National Park. The combination of knowledge I gained from mycological and herpetological research in Arizona provided a great platform for me to pursue my PhD at Arizona State University studying how a fungal pathogen affects Arizona amphibians.

I received a BS in biology and nutritional sciences and a minor in chemistry from the University of Arizona in 2011. After I graduated with my BS I spent two years working on numerous research projects studying species such as the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), desert tortoises (Gopherus agassizii), fungal endophytes (fungi that live inside plants), and several other herpertofauna species from the southwestern United States. I gained these experiences working with the University of Arizona, the Arizona Game and Fish Department and a not-for-profit group, Friends of Saguaro National Park. The combination of knowledge I gained from mycological and herpetological research in Arizona provided a great platform for me to pursue my PhD at Arizona State University studying how a fungal pathogen affects Arizona amphibians.

Evan Brus

I received my B.S in Zoology, French, and Environmental Studies from the University of Wisconsin Madison in 2011. During and after college, I worked in a social insect behavior lab studying the signals and cues that regulate nest construction in Polybia occidentalis, eventually traveling to Costa Rica to do research there. While studying for an ecology course, I happened upon the book Extinction in Our Times by my current advisor, James Collins. I was immediately intrigued by the story of amphibian declines, and I applied to do my PhD in his lab at ASU the following year.

I received my B.S in Zoology, French, and Environmental Studies from the University of Wisconsin Madison in 2011. During and after college, I worked in a social insect behavior lab studying the signals and cues that regulate nest construction in Polybia occidentalis, eventually traveling to Costa Rica to do research there. While studying for an ecology course, I happened upon the book Extinction in Our Times by my current advisor, James Collins. I was immediately intrigued by the story of amphibian declines, and I applied to do my PhD in his lab at ASU the following year.

Who would say has influenced you or your work?

Nick Massimo

I was inspired to pursue a career in biodiversity conservation by my early childhood experiences where I spent time with my family enjoying the great outdoors. Through these experiences I developed a deep appreciation of our beautifully complex natural world. The time I spent at the University of Arizona pursuing my BS continued to guide me to pursue a career in conservation due to some of my wonderful professors. Dr. Robichaux, Dr. Bonine and especially Dr. Arnold helped provide me with fantastic experiences and mentoring opportunities at the University of Arizona. Towards the end of my bachelor degree I received an internship with the Arizona Game and Fish Department. My advisor, David Grandmaison, introduced me to a wide array of projects focusing on conservation strategies for mammal, bird, reptile and amphibian species in Arizona.

After I graduated, I received a job with my most influential mentor, Dr. Betsy Arnold. During my time working with Dr. Arnold, I gained a large amount of experience on how to develop, conduct and conclude an intricate research project working with fungi that live inside of plants. Without the help and mentorship Dr. Arnold provided me, I would not be where I am today. Dr. Arnold has been my most influential mentor.

Evan Brus

Like many biologists and ecologists, I grew up with a deep appreciation for nature. I was lucky enough to live in a relatively rural area of Wisconsin surrounded by streams and forests, which I relished as a child. My early experiences exploring the outdoors informed my initial choice to study biology, but I credit several college professors for helping me refine my interests and encouraging my work. My undergraduate research mentor Dr. Robert Jeanne, as well as his grad students Ben Taylor and Teresa Schueller, taught me the culture of academia and the skills needed for data collection, analysis, and eventual publication. Without my experiences in this research group, I probably would not be a scientist today. My other major influence was Dr. Calvin DeWitt, who taught my introductory ecology course with fervent enthusiasm and took personal interest in all his students. I learned from him how to pursue my passions and how to visualize the myriad connections between humans and the natural world in everyday life. Currently, I draw inspiration from the broad community of scientists researching amphibian decline and chytridiomycosis, too many to name. The quantity and quality of research produced in our field is remarkable, and everyone is willing to help one another and collaborate. It’s a very welcoming and dedicated community.

Please share the details of your work: the medium, technique and discoveries.

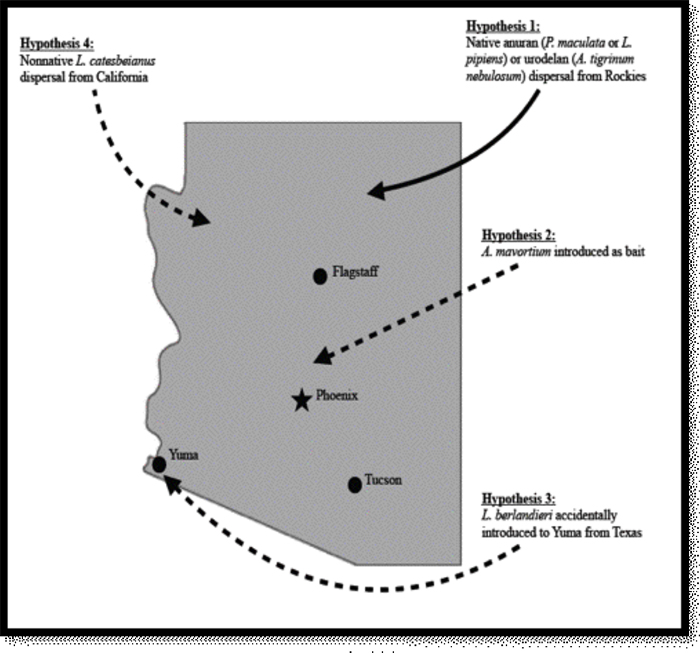

Our project will analyze how Bd may have been introduced into Arizona and how its introduction could have shaped Arizona amphibian distributions. In order to investigate these questions amphibian specimens housed in natural history collections will be assessed for the presence of Bd. Our work will determine at what time were certain species infected with Bd in the state, and do these historic infections help us understand the dramatic decline of leopard frog species in Arizona.

Our work will rely on testing amphibian skin for the presence of Bd DNA. In order to do this, we will swab amphibian specimens stored in natural history. DNA extractions will then be performed following protocols used by other researchers who have recently completed similar projects analyzing museum specimens. After DNA extractions are complete, real time PCR will be used to determine if fungal pathogen DNA is present and if so, quantify the pathogen load on the specimen. Once all of this data is collected we will gain an understanding of the disease dynamics of Bd in Arizona. This information will help determine when this deadly pathogen arrived in Arizona, what species of amphibians it infected after it arrived across time, and a possible mechanism that brought it to the state (e.g. invasive species, the bait trade etc.). Finally, this information will be used to help establish management plans to mitigate the spread of this pathogen in amphibian populations that are currently infected with Bd and also provide critical information on how to keep Bd out of populations that are currently uninfected.

We have not started our project yet. Other researchers who have recently completed similar projects have discovered Bd on amphibians in natural history collections in the past. Their work has helped us form our hypotheses on how Bd may have entered Arizona as it spread south into Mexico and Central America. Based off of a previous project we know that Bd was found on a Chiricahua Leopard Frog in Arizona as early as 1972. We would like to conduct an extensive project to discover the very important disease dynamics of Bd in Arizona, that’s why we are trying to raise funds for our research with the Instrumentl crowdfunding campaign (https://www.instrumentl.com/campaigns/history-of-a-deadly-disease-in-arizona-amphibians/).

What has been the most exciting discovery?

As we reviewed recent research conducted by other scientists we were intrigued to learn that this fungal pathogen has a very complex history. Unraveling the history of this extremely deadly amphibian disease is made even more moving as amphibians are the most threatened Class of vertebrates on the planet (IUCN Red List Report 2015). This information paired with recent research indicates that amphibians are experiencing extraordinarily high extinction rates currently than they have in the past. We find this information extremely motivating, as we’d like to conserve amphibian biodiversity for the well being of ecosystems and for our future generations.

What are some challenges you have faced and how did you deal with them?

The biggest challenge we are currently facing is obtaining funding to conduct this important project. The scientific field as a whole has been experiencing a shortage of funds to carry out extremely important research projects, and our field is no different. To combat this issue, we are currently exploring new avenues to fund our research endeavors. This is where the crowdfunding campaign (https://www.instrumentl.com/campaigns/history-of-a-deadly-disease-in-arizona-amphibians/) comes into play. We are trying to reach out to our community more directly and get them engaged with our project. We’d like to communicate the challenge we, as scientists face, as well as the challenges amphibians are now incurring.

How do you reach your targeted audience?

Is it through your website, exhibitions, advertising or social media or another route? Which is most effective and why?

We are exploring a variety of options to engage our audience. We have been reaching out to our close colleagues, research and herpetology community directly through word of mouth and email to generate support for our project. Additionally, we have also used social media (Facebook and Twitter) to gain support for our research project. Both of these avenues have provided support for our project but we’d like to reach more people. To do this, we are contacting people and groups located within Arizona to convey that this project will directly impact the amphibian biodiversity of our state and in other parts of the world.

How do you keep the audience engaged over time?

We’ve created a Facebook group (https://www.facebook.com/groups/905234229573944/) to keep our audience up to date on the progression of our research project as it’s being conducted. This will keep our audience up to date on the current status of our project and the exciting discoveries we’re making. In addition to our Facebook group, we are also planning to present the results of our study in a scientific journal article and present this information to our community in a series of talks.

What can we do to inspire the next generation to want to help the environment and the wildlife?

The information we gain from completing this study will directly lend to the construction of effective amphibian biodiversity conservation strategies. Without the help from our next generation we are at risk of losing much of the amazing amphibian biodiversity on our planet. The Frogs Are Green organization could be a wonderful partner in helping us to spread our project to its supporters. We feel that this organization can help reach a younger and broader audience than we’ve been able to reach thus far. In order for the meaningfulness of our research to be effective we need our next generations to know about the wonderful and beautiful amphibian biodiversity our planet has to offer.

What can people do to help? Donate and/or share to your cause/work?

We would be most appreciative if individuals would pledge to share our campaign with friends and colleagues using social media. We hope to reach as many people as possible because we feel the current state of our planet’s amphibian biodiversity is at a critical point. As a community we need to act now to preserve these species to maintain healthy ecosystems and for future generations. Sharing our campaign would help us reach our goal however we would be extremely thankful if people would also donate to our project so we can conduct this extremely important research.